For more than a decade, China has been positioning itself at the forefront of fundamental physics research — openly competing with Europe’s CERN to construct the next generation of particle colliders. These colossal machines smash elementary particles together at near‑light speeds to uncover the universe’s deepest secrets, from the nature of the Higgs boson to the mysteries of dark matter. But now, China has hit the brakes on its most ambitious collider project, citing cost, shifting priorities, and global competition.

The Vision: A Collider Bigger Than Anything Before

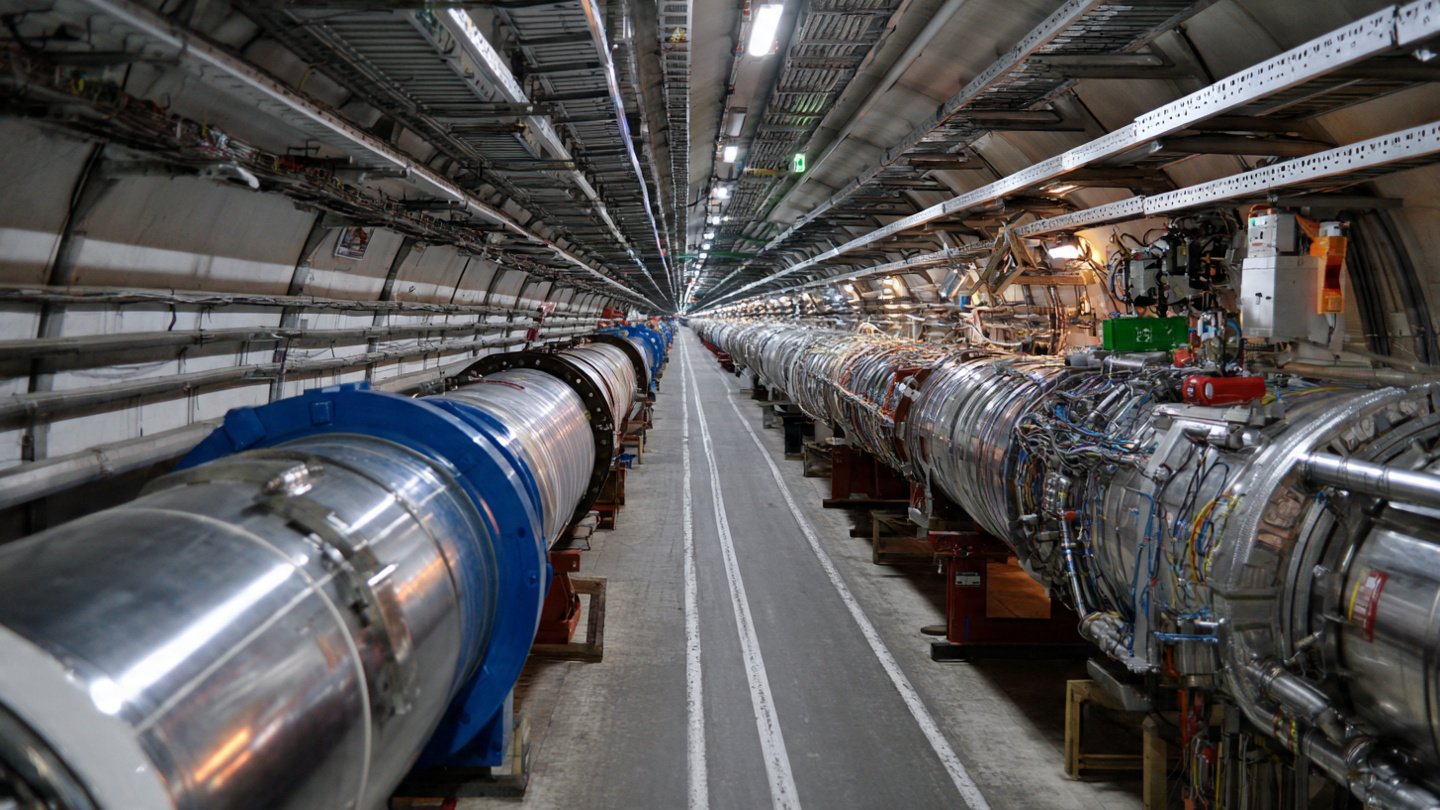

The centerpiece of China’s plans was the Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC), a proposed particle accelerator with a circumference of about 100 kilometers (62 miles) — nearly four times the size of the current world record holder, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva.

Designed primarily as a “Higgs factory”, the CEPC would accelerate electrons and their antiparticles (positrons) around a vast underground ring and smash them together at extremely high energies. These collisions would generate millions of Higgs bosons, allowing scientists to measure their properties with unprecedented precision and search for phenomena beyond the Standard Model of particle physics — potentially revealing new particles, fundamental forces, or insights into dark matter.

When first proposed by China’s Institute of High Energy Physics in 2012, the project was seen as a strategic leap: not merely a scientific experiment but a bold bid to leapfrog in global science leadership. Some physicists even suggested China could have such a machine running before Europe’s next generation collider — the Future Circular Collider (FCC).

Yet this race may now be over before it began.

Why the Project Was Halted

In late 2025, Chinese authorities made a quiet but significant decision: the CEPC was not included in the country’s next five‑year economic plan, effectively pausing its development.

According to reports, the project’s multibillion‑dollar price tag was a central concern for policymakers. Estimates put the total cost for the CEPC well into the tens of billions — far higher than initial projections — and expensive even by China’s already massive scientific investments. The sheer scale of construction, excavation, and technological infrastructure required was beginning to look like a “bottomless pit” of resources with uncertain returns.

Prominent Chinese physicists voiced mixed opinions within the scientific community. Supporters argued the CEPC could transform China into the hub of particle physics in Asia and attract global talent. Critics, including some respected scientists, questioned whether such an enormous investment was justified, especially given competing national priorities such as energy research, space exploration, and public health technologies.

The Strategic Shift

Instead of full‑scale construction, Chinese planners are now reported to be favoring a smaller, lower‑energy collider project that would still provide valuable scientific data but at a fraction of the cost. This scaled‑down version is expected to appear in future planning cycles, with government reevaluation possible after 2030.

The Institute of High Energy Physics has indicated it will resubmit the CEPC proposal in 2030 if Europe’s competing FCC project has not already gained official approval. In that case, Chinese physicists might opt to join the FCC collaboration rather than pursue an independent CEPC — a notable shift from earlier ambitions of outright leadership.

Implications for the Global Physics Community

A Win for Europe?

CERN and the European physics community have reacted positively to China’s pause. Fabiola Gianotti, Director‑General of CERN, described China’s decision as providing an “opportunity” for Europe’s own competing project — the Future Circular Collider (FCC) — to move forward without the pressure of a fast‑closing rival.

The FCC is planned as a roughly 91‑kilometer ring straddling the French‑Swiss border. With an estimated cost of $17 billion, it is one of the most expensive scientific projects ever proposed in Europe. Its goals include exploring dark matter, dark energy, and other fundamental questions that extend beyond the capabilities of the current Large Hadron Collider.

With China stepping back, some argue Europe could solidify its position as the global leader in collider physics — although the FCC still faces funding and approval hurdles from its member states.

China’s Broader Scientific Agenda

China’s retreat from the CEPC does not indicate a reduction in its overall commitment to advanced science. The country continues to invest heavily in other major scientific facilities and research programs. Recent progress includes:

- The High Intensity heavy‑ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF) in Guangdong, a large particle accelerator network expected to conduct advanced nuclear physics experiments by the end of 2025.

- The Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO), which is producing new experimental results in neutrino physics.

- New high‑energy light sources in Beijing capable of generating X‑ray beams trillions of times brighter than the sun — tools that benefit materials science, biology, and chemistry.

This suggests that while the CEPC may be on hold, China is still building research capacity across a wide range of disciplines, balancing ambitions with financial realism.

What Comes Next?

The pause of the CEPC project leaves several open questions for the future of particle physics:

- Will the CEPC be revived after 2030? Chinese scientists have said they plan to resubmit the project if current European plans are delayed.

- Will China collaborate with Europe’s FCC? If the FCC gains approval first, Chinese physicists may choose to join the European experiment rather than build a competing machine.

- How will global funding priorities shift? With many nations investing in advanced science — from fusion energy to quantum technologies — large collider projects will likely compete with other “big science” initiatives for government support.

For now, the story of the world’s largest particle collider has taken an unexpected turn: even a scientific powerhouse like China must reckon with the realities of cost, politics, and long‑term planning. What seemed just a few years ago like a sure‑fire race to surpass Europe now stands as a cautionary example of how ambitious science projects contend with fiscal and strategic limits.