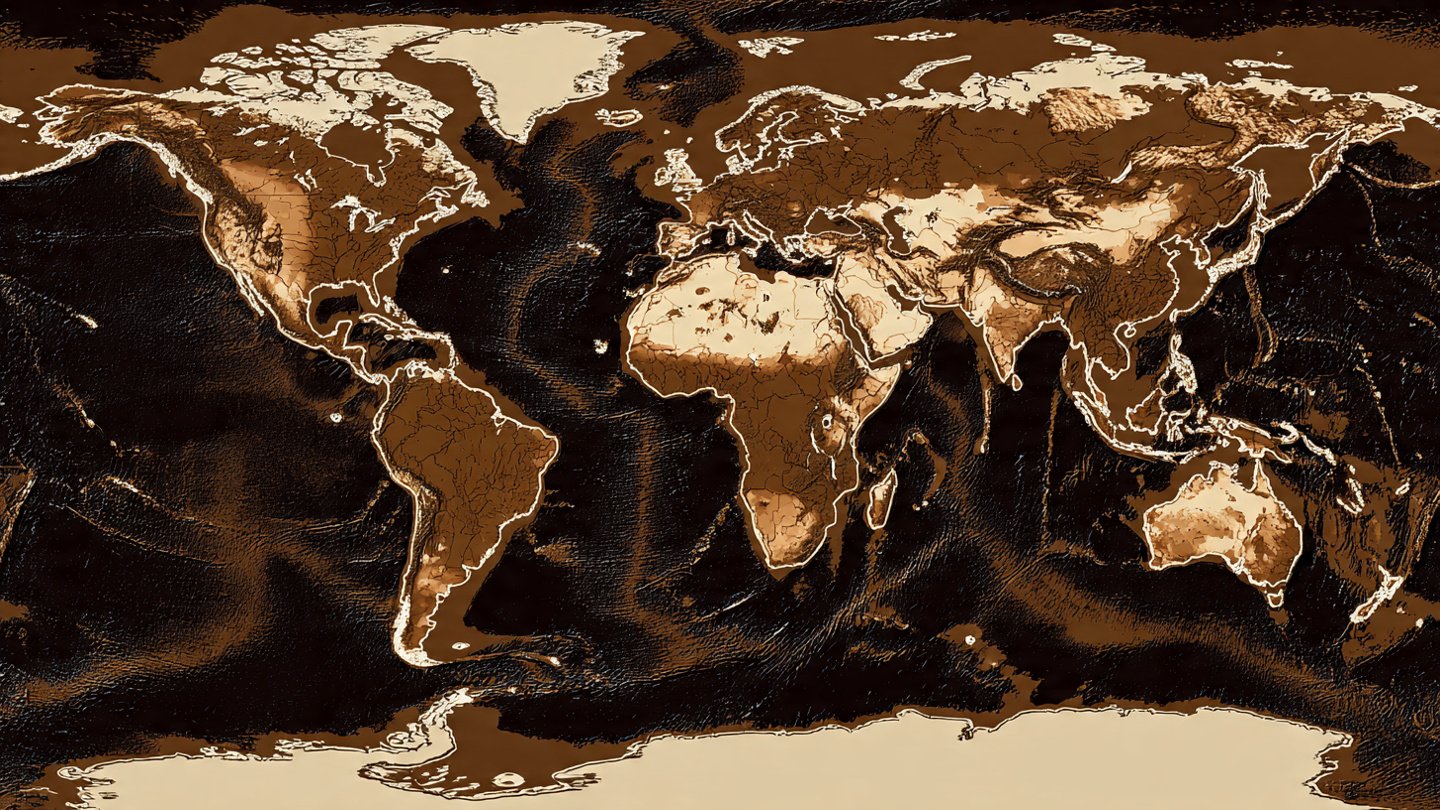

In recent years, satellites orbiting Earth have captured an astonishing and troubling image: a giant brown ribbon stretching across the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa toward the Americas, spanning thousands of kilometres and visible from space. What might look like a strange oceanic serpent is, in reality, a massive bloom of brown seaweed — and scientists say it’s not just a curiosity; it’s a red flag for the health of Earth’s oceans and climate.

This amazing phenomenon, sometimes described in media as stretching almost as long as an entire continent, is known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB) — a vast mat of seaweed that has grown to become the largest ever recorded.

What Is This Brown Ribbon?

The “brown ribbon” visible from space is primarily composed of Sargassum, a type of brown macroalgae (seaweed) that naturally floats on the ocean’s surface. Unlike many seafloor‑rooted seaweeds, Sargassum freely drifts — held aloft by tiny gas‑filled sacs that keep it afloat as it travels with ocean currents.

Historically, Sargassum was mostly confined to a region of the central Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. There, it served as a critical habitat for a variety of marine life, including fish, crabs, sea turtles, and juvenile eels, offering food and refuge in the open ocean.

But over the past decade and a half, the behaviour of this algae has changed dramatically. Instead of remaining in one region, vast quantities of Sargassum are now spreading outward and congregating into mats that stretch thousands of kilometres, forming what scientists call the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.

How Big Is It?

The scale of this phenomenon is staggering. Satellite data show that the Sargassum belt can extend over 8,500–8,800 kilometres — roughly from the west coast of Africa across the Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. For perspective, that is a distance greater than the breadth of the continental United States.

Beyond mere length, the sheer volume is striking: at certain points, scientists estimate that tens of millions of tons of algae are floating on the ocean’s surface during peak bloom periods.

Why Is It Happening Now? The Science Behind the Growth

The rapid emergence and expansion of the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is not random. A combination of natural and human‑influenced factors appear to be at work:

1. Changes in Ocean Currents and Climate Patterns

Ocean circulation patterns — including shifts in wind and currents influenced by climate variability — help push Sargassum mats out from their typical habitats and into nutrient‑rich tropical waters where they thrive. One study found that certain atmospheric and oceanic conditions around 2009–2010 effectively “tipped” Sargassum into tropical regions where it could grow unchecked.

2. Warmer Ocean Temperatures

Rising sea surface temperatures, linked to global climate change, create ideal conditions for Sargassum to grow more rapidly and survive longer. Warm waters accelerate algal growth and encourage reproduction, helping sustain the massive blooms observed today.

3. Excess Nutrients Feeding Growth

An influx of nutrients — particularly nitrogen and phosphorus — flowing from major rivers like the Amazon, Congo and Mississippi into the Atlantic Ocean acts like fertilizer for Sargassum. Agricultural runoff, untreated wastewater and warm dust from the Sahara Desert all contribute nutrients that fuel seaweed growth.

The confluence of increased nutrients with favourable currents and warm temperatures creates “perfect storm” conditions for Sargassum to flourish. Many scientists say this combination has tipped the Atlantic ocean into a new ecological state driven by human‑influenced changes.

From Ecosystem Component to Environmental Hazard

In modest quantities, floating Sargassum serves as a valuable ecological habitat in the open ocean. However, when blooms grow excessively large and consistent, they become a problem rather than a resource.

1. Ecosystem Disruption

Massive mats of Sargassum can block sunlight from penetrating the water’s surface. This deprives underwater seagrasses, coral reefs and mangroves of the sunlight they need to photosynthesize and survive. Over time, this can lead to significant loss of habitat for many species that depend on these ecosystems.

2. Impacts on Marine Life

As Sargassum decomposes, particularly along coastlines, it alters water quality by reducing oxygen levels and changing pH — conditions that can stress or kill fish and aquatic invertebrates. The decomposition process also releases noxious gases like hydrogen sulphide, which can irritate human lungs and eyes and create foul odours.

3. Coastal Economic Consequences

Communities that depend on tourism face serious challenges when beaches are blanketed by rotting seaweed. The smell, visual blight and difficulty of cleanup can deter visitors — leading to lost income and high management costs for local governments and businesses. This is especially impactful in regions like the Caribbean, Mexico and parts of West Africa.

A Sign of Broader Environmental Stress

While the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is visible from space and dramatic to behold, the consequences run deep.

Scientists warn that the belt’s regular and growing presence is a symptom of larger shifts in Earth’s climate and ocean systems. The unusual scale of Sargassum blooms suggests that the tropical Atlantic Ocean’s nutrient balance, temperature patterns, and circulation dynamics are being altered — likely due to a combination of climate change, land use changes, and increased nutrient loads from human activity.

Furthermore, the phenomenon highlights how interconnected terrestrial and ocean ecosystems are: what we do on land — how we farm, manage wastewater, and emit greenhouse gases — can have massive ripple effects across the ocean basin.

Some scientists also point out that the recurring blooms may be becoming a “new normal” in the Atlantic, driven by conditions that are now more favourable for Sargassum growth than at any other time in recent decades.

Is There Any Hope? Monitoring and Responses

Addressing the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is not simple, but awareness and scientific monitoring are improving:

- Satellites and advanced ocean models now allow near‑real‑time tracking of Sargassum extent and movement, giving coastal communities early warning of incoming blooms.

- Researchers are exploring ways to repurpose Sargassum biomass, including for fertilizers and construction materials, though scaling such solutions remains challenging. (Reddit discussions reflect interest in potential uses despite limitations.)

- Governments and environmental groups in affected regions are collaborating on response strategies, from cleanup operations to broader environmental policy responses.

Yet experts emphasize that long‑term solutions must address the root causes of the phenomenon — particularly climate change and nutrient pollution — if the belt is to shrink rather than continue growing.

Conclusion: What the Brown Ribbon Tells Us

The emergence of a continent‑sized brown ribbon of Sargassum across the Atlantic is more than a remarkable natural spectacle — it’s a clear indication that Earth’s oceans are undergoing profound changes. What once was a localized habitat for marine life has become a sprawling ecological challenge with consequences for ecosystems, economies, and climate feedback loops.

Scientists warn that this is not an isolated occurrence but a symptom of broader environmental disruptions linked to human activity. The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt underscores how deeply intertwined our actions are with the planet’s health — and how ocean ecosystems are among the first and most visible responders to changes in climate and nutrient cycles.

As this brown ribbon continues to stretch across the ocean, scientists and policymakers alike see it not as a curiosity, but as a cautionary sign — one that demands a deeper understanding of Earth’s changing environment and urgent efforts to protect its fragile balance.